More Information

Submitted: December 22, 2022 | Approved: January 05, 2023 | Published: January 06, 2023

How to cite this article: Slaoui A, Lazhar H, Amail N, Zeraidi N, Lakhdar A, et al. Meigs syndrome: About an uncommon case report. Clin J Obstet Gynecol. 2023; 6: 010-013.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.cjog.1001120

Copyright License: © 2023 Slaoui A, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Meigs syndrome; Tumoral markers; Ovarian fibroma

Abbreviations: CA 125: Cancer Antigen 125; HE-4: Human Epididymis protein 4; ROMA: Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm; BMI: Body Mass Index; CT: Computerized; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Meigs syndrome: About an uncommon case report

Aziz Slaoui1,2*, Hanaa Lazhar2, Noha Amail2, Najia Zeraidi2, Amina Lakhdar2, Aicha Kharbach1 and Aziz Baydada2

1Gynecology-Obstetrics and Endoscopy Department, Maternity Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed V, Rabat, Morocco

2Gynecology-Obstetrics and Endocrinology Department, Maternity Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed V, Rabat, Morocco

*Address for Correspondence: Aziz Slaoui, Gynecology-Obstetrics and Endoscopy Department, Maternity Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed V, Rabat, Morocco, Email: [email protected]

Background: Ovarian fibroma is a very unusual epithelial tumor representing less than 1% of all ovarian tumors. It can be asymptomatic and discovered during surgery or be associated with a pleural effusion preferentially located on the right side and a more or less abundant free ascites in the framework of the so-called Meigs syndrome. The challenge of management then lies in distinguishing benign from malignant since clinically, radiologically, and biologically everything points towards malignant which requires radical surgical treatment. We report here the case of a 69-year-old postmenopausal patient with a clinical form of Meigs' syndrome that strongly suggested ovarian cancer.

Case presentation: We hereby report here the case of a 69-year-old patient, menopausal, gravida 4 para 3 with 3 live children delivered vaginally and one miscarriage. She presented with ascites, hydrothorax, and a solid tumor of the ovary. Serum CA 125 and HE 4 levels were very high. ROMA score was highly suggestive of malignancy. A hysterectomy with adnexectomy was performed. It was only the histological evidence of ovarian fibroma and the rapid resolution of its effusions that confirmed Meigs syndrome.

Conclusion: Meigs syndrome is an anatomical-clinical entity that associates a benign tumor of the ovary, ascites, and hydrothorax. Highly elevated CA 125 and HE-4 tumor markers often point clinicians toward a malignant tumor and compel radical surgical treatment. This case report reminds us once again that only histology confirms the diagnosis of cancer.

Epithelial tumors of the ovary are very diverse in nature and often pose difficult diagnostic problems [1]. On the one hand, it is necessary to be able to confirm their organic nature in order not to over-treat a functional lesion, and on the other hand, it is also necessary to be able to assess their benign or malignant nature. Among them, we can mention the fibroid of the ovary which is a very unusual tumor representing less than 1% of all ovarian tumors [1]. Ovarian fibroma may be asymptomatic and discovered during surgery or it may be associated with a pleural effusion preferentially located on the right side and a more or less abundant free ascites in the so-called Meigs syndrome. We herein report the case of a 67-year-old menopausal patient with a clinical form of Meigs syndrome that strongly suggested ovarian cancer.

We hereby report here the case of a 69-year-old patient, menopausal, gravida 4 para 3 with 3 live children delivered vaginally and one miscarriage. She had been operated on for ovarian torsion in her childhood treated by left adnexectomy and given the delay in management and ovarian necrosis. She presented to our facility with dyspnea, uncounted weight loss, fatigue, cough, abdominal pain, and constipation. At our admission examination, the patient's general condition was altered by asthenia. She was polygenic at 28 cycles per minute and her blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg. Her weight and height were respectively 67 kg and 1.63 m with a BMI of 26.2. The abdominal examination was marked by abdominal bloating and diffuse dullness. The speculum examination revealed a healthy cervix and the vaginal touch coupled with the abdominal palpation revealed a mobile and solid right latero-uterine mass. Ultrasound examination showed abundant ascites, a uterus of normal size and morphology associated with a heterogeneous, poorly delineated right latero-uterine tissue mass of about 142 x 95 mm. The ascites fluid was transudate. The thoracic-abdominal-pelvic CT scan revealed the presence of a right basal pleural effusion, a large intraperitoneal effusion, and a large right pelvic fleshy mass 160 mm in the transverse axis and 100 mm in the anteroposterior axis, appearing to originate from the right adnexa. Biologically, the tumor markers were highly increased with CA 125 at 1028.3 IU/l, while HE-4 was 122.1 pmol. ROMA score was strongly suggestive of malignancy.

In view of the clinical and paraclinical context, the diagnosis of Meigs syndrome was evoked but ovarian cancer was also strongly feared. Thus, a preoperative paraclinical workup was proposed for surgery and came back normal.

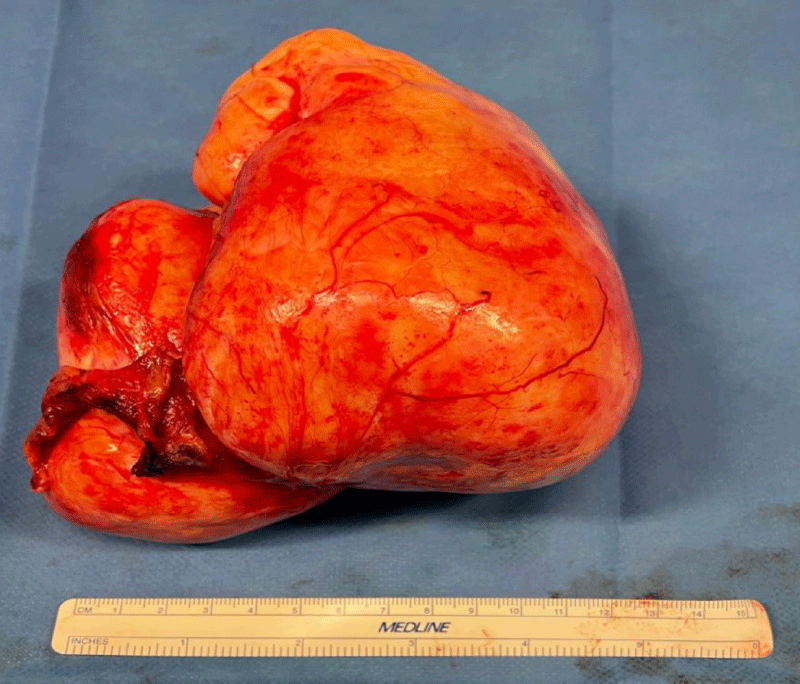

After obtaining the patient's written consent, an exploratory laparotomy by median approach was performed under general anesthesia. On exploration, we found very abundant ascites formed by a citrine yellow liquid of about 2.5 liters; a large ovoid pedicled ovarian tumor at the expense of the right ovary measuring 22 cm long axis and 15 cm short axis, bumpy, irregular surface, firm consistency, pearly white appearance, overhanging the uterus, more or less twisted but easily mobilizable without any adhesion. A careful exploration did not find any peritoneal carcinosis. Nevertheless, in view of the strong suspicion of malignancy, we performed a hysterectomy with right adnexectomy associated with an omentectomy, an appendectomy, and biopsies of the diaphragmatic cupolas (Figure 1). The large tumor removed was hard, smooth, and yellowish in color, measuring 16 cm x 14 cm, and weighing 1350 g (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Photography of the total hysterectomy specimen without adnexal preservation showing a hard, smooth, yellowish tumor developed in front of the right ovary, measuring 15 cm in diameter.

Figure 2: Photography of the tumor removed measuring 16 cm x 14 cm, hard, smooth and yellowish in color.

The surgical specimens were sent to a histopathology laboratory. Pathological examination of the surgical specimen showed macroscopically a firm greyish solid tumor and microscopically a connective tissue tumor consisting of small regular spindle cells forming intersecting bundles and corresponding to a fibroid of the ovary. The rest of the biopsies were free of any malignancy. The postoperative course was uneventful. There was a very remarkable clinical recovery with the disappearance of signs and drying of the pleural and peritoneal effusions. The patient was discharged after 6 days of hospitalization. Postoperative follow-up at 6 and 12 months was strictly normal.

Demons-Meigs syndrome was first described by Spiegel Berg in 1866 [2]. Demons, et al. in 1887 provided a patho-physiological explanation for the presence of hydrothorax and Meigs 1954 published 84 cases [2-5]. It is a very uncommon anatomical-clinical entity that occurs in 0.25% of ovarian tumors and most often affects women in the pre-and post-menopausal period, between the ages of 40 and 50 [6]. In its typical form, it groups together the Funck-Brentano conditions which are three [7]. First, there are anatomical/clinical conditions with the association of pleurisy, ascites, and ovarian fibroid. Then, there are the evolutionary conditions with recurrence of the pleural effusion after puncture and its drying up after. Finally, the physico-chemical conditions are defined by an identical pleural and ascitic fluid, in the form of a serofibrinous transudate without germs or neoplastic cells. The pleural effusion is located on the right in almost 65% of cases; however, an effusion on the left (15%) or bilaterally (20%) is possible [8,9]. Meig's syndrome has a favorable prognosis, with recovery without sequelae after the removal of the ovarian tumor [9]. Our observation strictly meets the definition of the Demons-Meigs syndrome, by the association of an ovarian fibroid, ascites, and hydrothorax and by the perfect recovery after surgical removal.

The pathophysiology of ascites and hydrothorax in Demons-Meigs syndrome is still debated and remains hypothetical. The vascular (venous and lymphatic) theory seems to be more convincing because it is unicast, although several pathophysiological hypotheses have been put forward. In 1944, Dockerty, et al. [10] explained the appearance of ascites by a partial obstruction of venous return, linked to a torsion of the pelvic tumor. The serous fluid then transudates through the capsule. For Meigs, et al. [11,12], the genesis of ascites is explained by an increase in pressure in the intratumoral lymphatics causing fluid to leak through the peritoneum. The passage of peritoneal fluid to the pleural cavity is thought to be via transdiaphragmatic lymphatic channels. This network is more developed on the right than on the left because of the liver mass, hence the right predominance of the pleural effusion. The ascites are thought to be caused by fluid loss due to tumor edema resulting from compression or torsion of the fibroid on its axis. In this case report, hydrothorax was also found on the right.

Ovarian fibromas are usually large tumors with an average size of 140 mm; the largest reported ovarian fibroma measured 300 mm × 200 mm × 100 mm [13]. Their macro-scopic appearance is very variable, most often a solid stromal tumor (as in our case) and more rarely a cystic tumor called cystadenofibroma [1]. Clinically, the major difficulty is to differentiate between ovarian fibroma and other solid ovarian tumors. Nevertheless, Meigs syndrome should always be considered in the presence of any ovarian tumor associated with ascites and pleural effusion [14].

Moreover, Meigs’ syndrome is not specific to ovarian fibroids as there are pseudo-Meigs syndromes [15], hence the major interest in pelvic ultrasound. In cystic ovarian tumors, it allows the benign or malignant character of the tumor to be approached with a sensitivity of 90% and a specificity of 87% [16,17]. But in solid tumors, as in our case, this sensitivity is less accurate because the images are more varied and less specific. The most frequent image of the ovarian fibroid is that of a solid hypodense polylobed mass without calcification. The performance of this morphological ultrasound is improved today by the use of Doppler, which allows the type of tumor to be better defined and has been shown to be useful [18]. CT and MRI give images that are no more specific than those observed on ultrasound. Their interest lies above all in the detection of peritoneal, diaphragmatic or epiploic carcinosis, the absence of which is an important element pointing to benignity in this context [15].

The contribution of tumor markers remains to be discussed. CA 125 elevation in ovarian fibroma was first reported by O'Connel, et al. in 1987 [19] and all cases published thereafter have been associated with elevated CA 125 [13,15,20-23] with a mean of 1200 IU/l and extremes of 286 IU/l [22] and 2360 IU/l [20]. The level found in our observation is within this range. Overall, the levels recorded in ovarian fibroids are much higher than those observed in ovarian cancers [2]. This association of ovarian fibroids with a significant elevation of CA 125 is a finding that is still open to discussion as to its pathophysiological explanation. Rouzier, et al. [15] suggested an attempt at an explanation by formulating the hypothesis that this hypersecretion of CA 125 would be of mesothelial origin and related to mechanical irritation (for example a torsion) or an increase in intraperitoneal pressure. To date, the marker HE-4 has only been studied once by Danilos, et al. [24] who, like us, observed high service levels with a very favorable ROMA score for malignancy. Although the latter may have contributed greatly to the better management of ovarian cancer, we have reached its limits here.

Finally, mistakenly considered a malignant tumor, we opted, as many authors before us, for radical treatment which proved to be useless [7,15]. Favorable spontaneous evolution showed that Meigs syndrome closely mimics ovarian neoplasia and proves that the existence of ascites and/or pleural effusion are not necessarily synonymous with malignancy in the presence of an ovarian tumor [25]. Again, only histological evidence confirms ovarian cancer. More recently, two cases of death associated with Meigs syndrome have been described [26,27]. The relatively good prognosis should not lead to a lack of vigilance in the management of the disease and practitioners should always consider any ovarian tumor with caution and manage it promptly and thoroughly.

Meigs syndrome is an anatomical-clinical entity that associates a benign tumor of the ovary, ascites, and hydrothorax. Highly elevated CA 125 and HE-4 tumor markers often point clinicians toward a malignant tumor and compel radical surgical treatment. This case report reminds us once again that only histology confirms the diagnosis of cancer.

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [28].

Declarations

Ethical approval: Ethics approval has been obtained to proceed with the current study.

Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Author contribution: AS: study concept and design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation, and writing the paper. HL: study concept, data collection, data analysis, and writing the paper. NA: study concept, data collection, data analysis, writing the paper. NZ: study design, data collection, data interpretation, writing the paper. AL: study design, data collection, data interpretation, writing the paper. AB: study design, data collection, data interpretation, writing the paper. AK: study concept, data collection, data analysis, writing the paper.

Guarantor of submission: The corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Availability of data and materials: Supporting material is available if further analysis is needed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

- Philippe E, Duvillard P. Tumeurs du revêtement épithélial de l'ovaire. Anatomie pathologique [Tumors of the ovarian epithelium. Pathological anatomy]. Rev Prat. 1993 Sep 1;43(13):1735-7. French. PMID: 8303200.

- Meigs JV, Cass JW. Fibroma of the ovary with ascite and hydrothorax. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1937; 33 (2): 249-67.

- LEGER L. Fibrome de l'ovaire avec ascite et hydrothorax; syndrome de Meigs [Ovarian fibroma with ascites and hydrothorax; Meigs syndrome]. Presse Med (1893). 1947 Jan 25;55(6):64-6. French. PMID: 18918018.

- Bretelle F, Portier MP, Boubli L, Houvenaeghel G. Syndrome de Demons-Meigs récidivé. A propos d'un cas [Recurrence of Demons-Meigs' syndrome. A case report]. Ann Chir. 2000 Apr;125(3):269-72. French. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4001(00)00128-8. PMID: 10829508.

- Démons A. Epanchements pleurétiques compliquantles kystes de l’ovaire. Bull Mem Soc Chi Paris. 1887; 13:771-6.

- Sfar E, Ben Ammar K, Mahjoub S, Zine S, Kchir N, Chelli H, Khrouf M, Chelli M. Caractéristiques anatomo-cliniques des tumeurs fibrothécales de l'ovaire. A propos de dix-neuf cas en douze ans: 1981-1992 [Anatomo-clinical characteristics of ovarian fibrothecal tumors. 19 cases over 12 years: 1981-1992[]. Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1994 Jun;89(6):315-21. French. PMID: 8085103.

- FUNCK-BRENTANO P. Limitation et extension du syndrome de Demons-Meigs [Limitation and Extension of Demons-Meigs Syndrome]. Presse Med (1893). 1949 Apr 16;57(25):341. French. PMID: 18120226.

- Geraads A, Tary P, Cloup N. Syndrome de Demons-Meigs dû à un goitre ovarien [Demons-Meigs syndrome caused by ovarian goiter]. Rev Pneumol Clin. 1991;47(4):194-6. French. PMID: 1775877.

- Vaillant G, Fade O, Royer E, Simon G, Orvain E. Lespleurésies ovariennes. Med et hyg 1985; 43: 3686-9.

- Dockerty MB, Masson JC. Ovarian Fibromas: a clinical and pathologic study of two hundred and eighty-three cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1944; 47: 741-52.

- Meigs JV, Armstrong SH, Hamilton HH. A further contribution to the syndrome of fibroma of the ovary with fluid in the abdomen and chest, Meigs' syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1943;46:19-37.

- Berthiot G, Belair F, Marcon JM, Body G, QuinquenelMC, Boudouin R. Syndrome de Demons-Meigs. Concoursmed 1989; 111:427-431.

- Timmerman D, Moerman P, Vergote I. Meigs' syndrome with elevated serum CA 125 levels: two case reports and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 1995 Dec;59(3):405-8. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1995.9952. PMID: 8522265.

- MEIGS JV. Fibroma of the ovary with ascites and hydrothorax; Meigs' syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954 May;67(5):962-85. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(54)90258-6. PMID: 13148256.

- Rouzier R, Berger A, Cugnenc PH. Syndrome de Demons-Meigs: peut-on faire le diagnostic en pré-opératoire? [Meigs' syndrome: is it possible to make a preoperative diagnosis?]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1998 Sep;27(5):517-22. French. PMID: 9791579.

- Granberg S, Wikland M. Ultrasound in the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cystic tumours. Hum Reprod. 1991 Feb;6(2):177-85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137301. PMID: 2056016.

- Benacerraf BR, Finkler NJ, Wojciechowski C, Knapp RC. Sonographic accuracy in the diagnosis of ovarian masses. J Reprod Med. 1990 May;35(5):491-5. PMID: 2191131.

- Marret H. Echographie et doppler dans le diagnostic des kystes ovariens: indications, pertinence des critères diagnostiques [Doppler ultrasonography in the diagnosis of ovarian cysts: indications, pertinence and diagnostic criteria]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2001 Nov;30(1 Suppl):S20-33. French. PMID: 11917373.

- O'Connell GJ, Ryan E, Murphy KJ, Prefontaine M. Predictive value of CA 125 for ovarian carcinoma in patients presenting with pelvic masses. Obstet Gynecol. 1987 Dec;70(6):930-2. PMID: 3479735.

- Walker JL, Manetta A, Mannel RS, Liao SY. Cellular fibroma masquerading as ovarian carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Sep;76(3 Pt 2):530-1. PMID: 2381641.

- Lin JY, Angel C, Sickel JZ. Meigs syndrome with elevated serum CA 125. Obstet Gynecol. 1992 Sep;80(3 Pt 2):563-6. PMID: 1495739.

- Le Bouëdec G, Glowaczower E, de Latour M, Fondrinier E, Kauffmann P, Dauplat J. Le syndrome de Demons-Meigs. A propos d'un fibrothécome et d'un fibrome ovariens [Demons-Meigs' syndrome. A case of thecoma and ovarian fibroma]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 1992;21(6):651-4. French. PMID: 1331226.

- Siddiqui M, Toub DB. Cellular fibroma of the ovary with Meigs' syndrome and elevated CA-125. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1995 Nov;40(11):817-9. PMID: 8592321.

- Danilos J, Michał Kwaśniewski W, Mazurek D, Bednarek W, Kotarski J. Meigs' syndrome with elevated CA-125 and HE-4: a case of luteinized fibrothecoma. Prz Menopauzalny. 2015 Jun;14(2):152-4. doi: 10.5114/pm.2015.52157. Epub 2015 Jun 22. PMID: 26327905; PMCID: PMC4498034.

- Kristková L, Zvaríková M, Bílek O, Dufek D, Poprach A, Holánek M. Meigs syndrome. Klin Onkol. 2022 Spring;35(3):232-234. English. doi: 10.48095/ccko2022232. PMID: 35760576.

- Tan N, Jin KY, Yang XR, Li CF, Yao J, Zheng H. A case of death of patient with ovarian fibroma combined with Meigs Syndrome and literature review. Diagn Pathol. 2022 Oct 17;17(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s13000-022-01258-9. PMID: 36253781; PMCID: PMC9575228.

- Barranco R, Molinelli A, Gentile R, Ventura F. Sudden, Unexpected Death Due to Pseudo-Meigs Syndrome: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2019 Mar;40(1):89-93. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000438. PMID: 30359338.

- Agha RA, Franchi T, Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Kerwan A; SCARE Group. The SCARE 2020 Guideline: Updating Consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines. Int J Surg. 2020 Dec;84:226-230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. Epub 2020 Nov 9. PMID: 33181358.