More Information

Submitted: December 22, 2022 | Approved: January 05, 2023 | Published: January 06, 2023

How to cite this article: Slaoui A, Bennani A, Tayeb R, Zeraidi N, Lakhdar A, et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy: A clinical case report. Clin J Obstet Gynecol. 2023; 6: 006-009.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.cjog.1001119

Copyright License: © 2023 Slaoui A, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Caesarean scar pregnancy; Conservative management; Methotrexate Injection

Abbreviations: Beta hCG: Beta human Chorionic Gonadotropin; MTX: Methotrexate; IVF: In vitro Fertilization; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Cesarean scar pregnancy: A clinical case report

Aziz Slaoui1,2*, Aicha Bennani1, Roughaya Tayeb2, Najia Zeraidi2, Amina Lakhdar2, Aziz Baydada2 and Aicha Kharbach1

1Gynecology-Obstetrics and Endoscopy Department, Maternity Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed V, Rabat, Morocco

2Gynecology-Obstetrics and Endocrinology Department, Maternity Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed V, Rabat, Morocco

*Address for Correspondence: Aziz Slaoui, Gynecology-Obstetrics and Endoscopy Department, Maternity Souissi, University Hospital Center IBN SINA, University Mohammed V, Rabat, Morocco, Email: [email protected]

Background: Among the different forms of ectopic pregnancy, cesarean scar pregnancy is one of the most uncommon with an estimated incidence of 1/1800 pregnancies. A major risk of massive hemorrhage, it requires active management as soon as it is diagnosed because it can affect the functional prognosis of the patient (hysterectomy) but can also be life-threatening. Different surgical techniques are generally proposed in first intention to patients who no longer wish to have children, who are hemodynamically unstable and/or in case of failure of medical treatment.

Case presentation: We hereby report the case of a young 19-year-old patient with no particular medical history, gravida 2 para 1 with a live child born after a cesarean section for fetal heart rhythm abnormalities during labor 5 months earlier and who presented to the emergency room of our structure for the management of a cesarean pregnancy scar diagnosed at 6 weeks of amenorrhea. She was successfully managed with an intramuscular injection of methotrexate. The follow-up was uneventful.

Conclusion: The implantation of a pregnancy on a cesarean section scar is becoming more and more frequent. With consequences that can be dramatic, ranging from hysterectomy to life-threatening hemorrhage, clinicians must be familiar with this pathological entity and be prepared for its management. The latter must be rapid and allow, if necessary, the preservation of the patient's fertility. In this sense, conservative medical treatment with methotrexate injections should be proposed as a first-line treatment in the absence of contraindication.

Among the different forms of ectopic pregnancy, cesarean scar pregnancy is one of the most uncommon with an estimated incidence of 1/1800 pregnancies [1]. A major risk of massive hemorrhage, it requires active management as soon as it is diagnosed because it can affect the functional prognosis of the patient (hysterectomy) but can also be life-threatening [1]. Different surgical techniques are generally proposed in first intention to patients who no longer wish to have children, who are hemodynamically unstable, and/or in case of failure of medical treatment. We hereby report the case of a young 19-years-old patient with no particular medical history, gravida 2 para 1 with a live child born after a cesarean section for fetal heart rhythm abnormalities during labor 5 months earlier and who presented to the emergency room of our structure for the management of a cesarean pregnancy scar diagnosed at 6 weeks of amenorrhea. Through this observation and in the light of a review of the literature, we will discuss the diagnostic and therapeutic characteristics of this rare entity, the knowledge of which the practitioners allows to improve the prognosis.

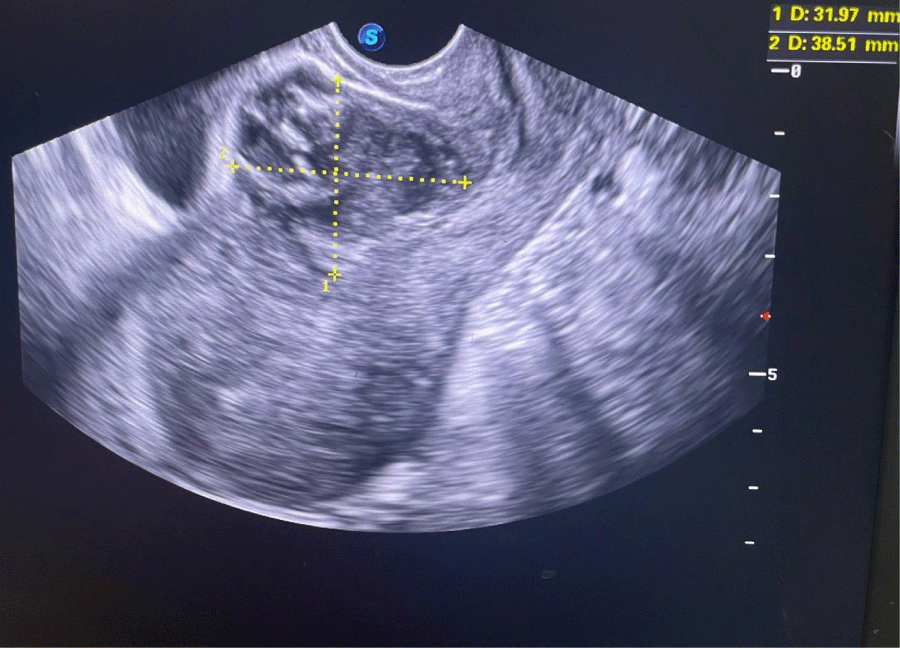

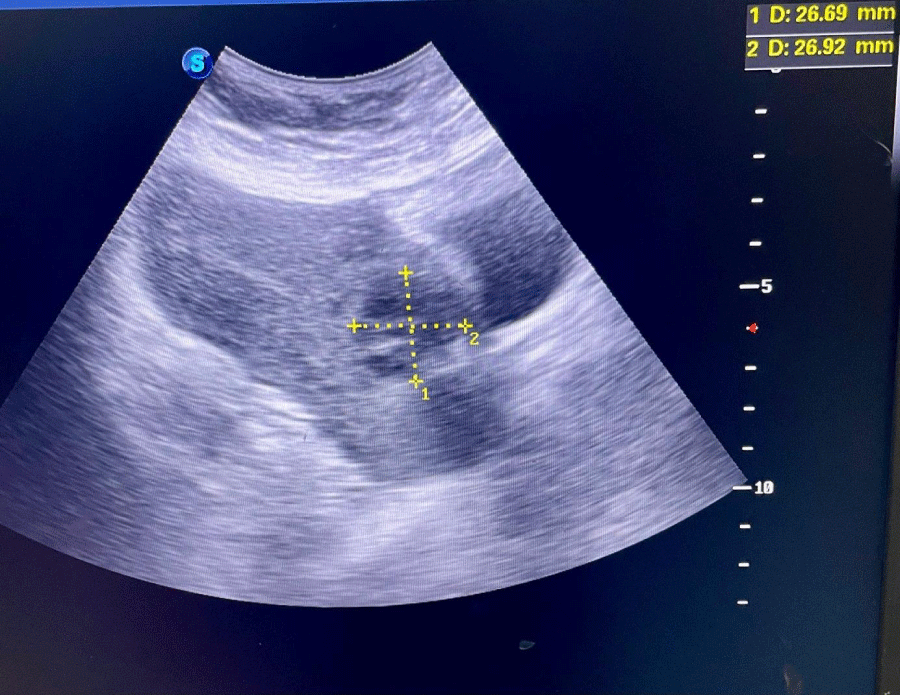

We hereby present the uncommon case of a 19-years-old female patient with no particular medical history, gravida 2 para 1 with a live child born after a cesarean section for breach presentation five months earlier, who presented to the gynecological emergency room with pelvic pain and blackish metrorrhagia of low intensity evolving for three days over an amenorrhea of 6 weeks. On clinical examination, the hemodynamic state was stable, abdominal palpation did not reveal any tenderness, speculum examination confirmed the endo-uterine origin of the bleeding, and vaginal touch combined with abdominal palpation showed a slightly enlarged uterus without any latero-uterine mass or signs of peritoneal irritation. A urine beta-hCG test confirmed a pregnancy. An abdominopelvic ultrasound performed in the emergency department showed a heterogeneous endouterine image measuring 38 by 32 mm low and located opposite the site of the c-section scar with respect to the bladder wall (Figures 1,2). We did not find any peritoneal effusion or latero-uterine image and the adnexa were of normal size and morphology.

Figure 1: Endovaginal ultrasound photography showing the cesarean pregnancy scar.

Figure 2: Sus-pubic ultrasound photography showing the same heterogeneous image at the level of the cesarean scar with respect to the bladder.

Following hospitalization, the patient was monitored clinically, radiologically, and biologically. The kinetics of beta hCG stagnated and went from 47 IU to 43 IU at 48 hours. The diagnosis of non-viable pregnancy on cesarean scar was therefore made. The decision of the staff was naturally directed towards medical treatment given her young age and beta hCG level. She received an intramuscular injection of 1 mg/kg or 57 mg of MTX. The beta hCG level decreased from 57 IU at D4 post-injection to 17 IU at D7.

Four weeks after the injection, the patient presented black metrorrhagia of low to medium severity with beta hCG plasma level negativation. Ultrasound control no longer found the heterogeneous image at the scar. The follow-up was uneventful.

First described in 1978 [2], the outcome of the first cases of cesarean scar pregnancy was often hemostasis hysterectomy in the face of hemorrhage caused by the first curettage treatment or spontaneous metrorrhagia without an etiological diagnosis. Nowadays, the incidence of pregnancy on cesarean section scars is estimated to be between 1/1800 and 1/2250 pregnancies [1,3]. With nearly 100 cases described in the literature since 1978, this initially exceptional ectopic pregnancy is increasing in frequency [3]. The incriminated risk factors are similar to those of placenta accreta: on the one hand, the number of previous cesarean sections and endo-uterine gestures (curettages, manual uterine revision), on the other hand, IVF techniques with embryo transfer are also discussed in the mechanism [1,4,5].

From a physiopathological point of view, a micro-defect of the hysterotomy scar would allow invasion of the uterine muscle by the blastocyst [6]. As these cesarean sections are often programmed, as in the case of our patient, the less solicited and less mature lower segment would not allow the optimal quality of healing and would favor ectopic implantation of the egg [6]. The specificity of our observation also arises from the short intergenic interval of 5 months which is not sufficient to allow an optimal quality of cicatrization.

Two clinical forms have been described, firstly shallow implantation in the scar with development towards the uterine cavity or towards the cervical-isthmic canal, and secondly deep implantation in the scar with development towards the bladder and towards the abdomen, the form most at risk of rupture [7,8]. Clinical manifestations include abdominal pain and bleeding, which can range from simple spotting to fatal hemorrhage [9]. However, the clinic can sometimes be asymptomatic; indeed, a series of studies found up to 40% of patients showed neither pain nor vaginal bleeding [9]. This is why it is important to pay attention to the patient's history. Delayed diagnosis may be the cause of the uterine rupture, and a diagnostic error and management as a miscarriage by curettage from the outset could lead to massive hemorrhage [9]. All this underlines the great importance of rapid and accurate diagnosis in improving the vital and functional prognosis [10].

The diagnosis is made by endovaginal ultrasound, as in our case. It is based on the criteria established by Vial, et al. in 2000 [11] associating an empty uterus; an empty cervical canal and finally the existence of a sagittal section of the uterus of a disruption of the gestational sac on the anterior uterine wall. Indirect ultrasound signs are a decrease in myometrial thickness between the gestational sac and the bladder, which reflects the depth of implantation, and peri-trophoblastic hypervascularization, which is objectified by color or energy Doppler [11]. At the early stage, there is usually no pelvic effusion or adnexal mass as in our case (otherwise, the pregnancy is probably already ruptured). Doppler is very useful to differentiate between viable and non-viable scar pregnancy [1], which is an important impact on subsequent management. In case of persistent diagnostic doubt after the ultrasound, other imaging examinations can be performed such as three-dimensional ultrasound or MRI, which allows understanding of the anatomical relationships by specifying the depth of trophoblastic invasion in the myometrium, and the potential involvement of the serosa or bladder as well as the exact position of the gestational sac [12]. Sagittal and transverse sections in T1 and T2 weighted sequence clearly show the ovarian sac located in the anterior wall of the uterus. This would allow a better appreciation of the volume of the lesion and guide the therapeutic choices [6,12]. If the diagnosis is obvious on two-dimensional ultrasound, these advanced examinations are not recommended [4].

Given the rarity of this situation, there are currently no formal recommendations regarding treatment modalities. Treatment is based on gestational age, available therapeutic means, the patient's desire for future fertility, the experience of the therapeutic team, and the complications of first-line therapy. Currently, treatment, whether medical or surgical, remains conservative, except in cases of therapeutic failure [13]. Medical treatment in a hemodynamically stable patient is possible for many teams [8,10-13]. It is based on the administration of methotrexate locally (injection in situ, possibly under ultrasound or coelioguidance) or systemically like our case or a combination of the two at a dose of 1 mg/kg [13]. The success rate is similar for both routes of administration and is in the order of 70% - 80% [8]. This treatment requires daily monitoring of the decrease in beta hCG during hospitalization and then once a week until negativation, with ultrasound monitoring until the complete disappearance of the ovarian sac, with an average time required for beta hCG negativation of 4 weeks to 6 weeks. The prognostic factors for failure of medical treatment would be beta hCG level higher than 10,000 IU/L, weeks of gestation higher than 9, presence of fetal heart activity on ultrasound, and craniocaudal length of the embryo greater than 10 mm on ultrasound.

The various surgical techniques are usually proposed as first-line treatment for patients who no longer wish to have a child, who are hemodynamically unstable, and in the event of failure of medical treatment [10]. Aspiration-curettage carries a risk of hemorrhage and uterine rupture: contraindicated blindly, it remains acceptable under ultrasound control in the case of a gestational sac developed towards the cavity. Hysteroscopic resection was first described in 2005 by Wang, et al. [14]. This procedure has the advantage of good visualization of the pregnancy and of allowing selective coagulation of the vessels located at the level of the selective coagulation of the vessels located at the implantation site. This prevents per and postoperative hemorrhagic complications [14]. Fertility is also preserved. However, the classic surgical treatment remains resection of the pregnancy with the repair of the hysterotomy, which also allows preventive hemostasis by ligation of the uterine or hypogastric arteries [10]. The laparoscopic approach is tending to replace laparotomy, but a great deal of surgical expertise is necessary to guarantee a quality myometrial suture [15,16].

Regarding the obstetrical prognosis, a few pregnancies have been described after any type of conservative treatment [17]. The risk of recurrence is estimated at 5% [18]. Some teams recommend a delay of 12 months to 24 months between pregnancy on a cesarean scar and a future pregnancy [18]. Some authors recommend evaluation of the cesarean scar, especially by hysterosonography, before considering another pregnancy [18,19]. It is then recommended to perform an early ultrasound in a subsequent pregnancy in order to verify the intrauterine location of the gestational sac [19]. The preferred delivery method would then be a scheduled cesarean section at 37 weeks of amenorrhea, in view of the increased risk of uterine rupture [17]. Our patient became pregnant again after 13 months and her current pregnancy is endo-uterine. A prophylactic cesarean section was suggested at 37 weeks of amenorrhea.

The implantation of a pregnancy on a cesarean section scar is becoming more and more frequent. With consequences that can be dramatic, ranging from hysterectomy to life-threatening hemorrhage, clinicians must be familiar with this pathological entity and be prepared for its management. The latter must be rapid and allow, if necessary, the preservation of the patient's fertility. In this sense, conservative medical treatment with methotrexate injections should be proposed as a first-line treatment in the absence of contraindication.

This work has been reported in line with the SCARE 2020 criteria [20].

Declarations

Ethical approval: Ethics approval has been obtained to proceed with the current study.

Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Author contribution: AS: study concept and design, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation, and writing the paper. AB: study concept, data collection, data analysis, writing the paper. RT: study concept, data collection, data analysis, and writing the paper. NZ: study design, data collection, data interpretation, writing the paper. AL: study design, data collection, data interpretation, and writing the paper. AB: study design, data collection, data interpretation, and writing the paper. AK: study concept, data collection, data analysis, writing the paper.

Guarantor of submission: The corresponding author is the guarantor of submission.

Availability of data and materials: Supporting material is available if further analysis is needed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

- Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ. First-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Mar;21(3):220-7. doi: 10.1002/uog.56. PMID: 12666214.

- Larsen JV, Solomon MH. Pregnancy in a uterine scar sacculus--an unusual cause of postabortal haemorrhage. A case report. S Afr Med J. 1978 Jan 28;53(4):142-3. PMID: 653492.

- Maheut L, Seconda S, Bauville E, Levêque J. Grossesse sur cicatrice de césarienne : un cas clinique de traitement conservateur [Cesarean scar pregnancy: a case report of conservative management]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2010 May;39(3):254-8. French. doi: 10.1016/j.jgyn.2010.02.003. Epub 2010 Mar 12. PMID: 20227196.

- Maymon R, Halperin R, Mendlovic S, Schneider D, Vaknin Z, Herman A, Pansky M. Ectopic pregnancies in Caesarean section scars: the 8 year experience of one medical centre. Hum Reprod. 2004 Feb;19(2):278-84. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh060. PMID: 14747167.

- Persadie RJ, Fortier A, Stopps RG. Ectopic pregnancy in a caesarean scar: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005 Dec;27(12):1102-6. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30392-9. PMID: 16524528.

- Gonzalez N, Tulandi T. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jul-Aug;24(5):731-738. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2017.02.020. Epub 2017 Mar 6. PMID: 28268103.

- Cox JT, Schiffman M, Solomon D; ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study (ALTS) Group. Prospective follow-up suggests similar risk of subsequent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 among women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 or negative colposcopy and directed biopsy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Jun;188(6):1406-12. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.461. PMID: 12824970.

- Morcel K, Seconda S, Voltzenlogel MC, Duros S, Chevallier J, Levêqye J. Gestion de la grossesse ectopique dans la cicatrice de cesarienne. Collège national des gynécologues et obstetriciens français.

- Noël L, Thilaganathan B. Caesarean scar pregnancy: diagnosis, natural history and treatment. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Oct 1;34(5):279-286. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000808. Epub 2022 Aug 22. PMID: 36036475.

- Gulino FA, Ettore C, Ettore G. A review on management of caesarean scar pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Oct 1;33(5):400-404. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000734. PMID: 34325464.

- Vial Y, Petignat P, Hohlfeld P. Pregnancy in a cesarean scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000 Nov;16(6):592-3. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00300-2.x. PMID: 11169360.

- Seow KM, Hwang JL, Tsai YL, Huang LW, Lin YH, Hsieh BC. Subsequent pregnancy outcome after conservative treatment of a previous cesarean scar pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004 Dec;83(12):1167-72. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00445.x. PMID: 15548150.

- Nawroth F, Foth D, Wilhelm L, Schmidt T, Warm M, Römer T. Conservative treatment of ectopic pregnancy in a cesarean section scar with methotrexate: a case report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001 Nov;99(1):135-7. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(01)00365-7. PMID: 11604205.

- Wang CJ, Yuen LT, Chao AS, Lee CL, Yen CF, Soong YK. Caesarean scar pregnancy successfully treated by operative hysteroscopy and suction curettage. BJOG. 2005 Jun;112(6):839-40. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00532.x. PMID: 15924549.

- Roche C, McDonnell R, Tucker P, Jones K, Milward K, McElhinney B, Mehrotra C, Maouris P. Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy: Evolution from medical to surgical management. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2020 Dec;60(6):852-857. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13241. Epub 2020 Aug 20. PMID: 32820539.

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Calì G, D'Antonio F, Kaelin Agten A. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Diagnosis and Pathogenesis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2019 Dec;46(4):797-811. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2019.07.009. PMID: 31677755.

- Imbar T, Bloom A, Ushakov F, Yagel S. Uterine artery embolization to control hemorrhage after termination of pregnancy implanted in a cesarean delivery scar. J Ultrasound Med. 2003 Oct;22(10):1111-5. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.10.1111. PMID: 14606570.

- Ben Nagi J, Helmy S, Ofili-Yebovi D, Yazbek J, Sawyer E, Jurkovic D. Reproductive outcomes of women with a previous history of Caesarean scar ectopic pregnancies. Hum Reprod. 2007 Jul;22(7):2012-5. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem078. Epub 2007 Apr 20. PMID: 17449510.

- Calì G, Timor-Tritsch IE, Palacios-Jaraquemada J, Monteaugudo A, Buca D, Forlani F, Familiari A, Scambia G, Acharya G, D'Antonio F. Outcome of Cesarean scar pregnancy managed expectantly: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Feb;51(2):169-175. doi: 10.1002/uog.17568. PMID: 28661021.

- Agha RA, Franchi T, Sohrabi C, Mathew G, Kerwan A; SCARE Group. The SCARE 2020 Guideline: Updating Consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines. Int J Surg. 2020 Dec;84:226-230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. Epub 2020 Nov 9. PMID: 33181358.