More Information

Submitted: 26 January 2020 | Approved: 11 August 2020 | Published: 12 August 2020

How to cite this article: Vargas-Hernández VM, Tovar-Rodríguez JM, Vargas-Aguilar VM. Endometriosis as a risk factor for colorectal cancer. Clin J Obstet Gynecol. 2020; 3: 093-097.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.cjog.1001057

Copyright License: © 2020 Vargas-Hernández VM, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Endometriosis; Eolorectal cancer; Neoplasms associated with endometriosis; Adenomyosis; Malignant transformation; Simulation

Endometriosis as a risk factor for colorectal cancer

Víctor Manuel Vargas-Hernández*, José María Tovar- Rodríguez and Víctor Manuel Vargas-Aguilar

Servicio de Ginecología, Hospital Juárez de México, SS, Clínica de Salud Femenina, Insurgentes Sur 605-1403, Nápoles, CDMX 03810 México

*Address for Correspondence: Víctor Manuel Vargas-Hernández, Servicio de Ginecología, Hospital Juárez de México, SS, Clínica de Salud Femenina, Insurgentes Sur 605-1403, Nápoles, CDMX 03810 México, Tel: (55) 52179782; (55) 55746647; Email: [email protected]

Endometriosis is a common benign disease in women of reproductive age, it has been associated with an increased risk of various malignancies that is defined by certain histological criteria mainly 80% in ovary and 20% in extragonadal sites such as intestine, rectovaginal septum, abdominal wall, pleura and others; the greatest risk for colorectal cancer is women with adenomyosis or endometriosis; Several genetic alterations have been found in the risk of endometriosis associated with cancer; The symptomatology, imaging and endoscopic characteristics simulate other inflammatory and malignant lesions that make the preoperative diagnosis of extragonadal endometriosis difficult. This is a review of the knowledge about endometriosis and its potential risk of malignancy, particularly with colorectal cancer

Endometriosis is a proliferative disease that is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity; or in extrauterine sites, it is a common chronic gynecological disease; the incidence in women of reproductive age is 5% to 17%, its cause is unknown; But, the accepted hypothesis is the implantation of endometrial tissue in the peritoneal cavity due to retrograde menstruation, or when endometrial tissues and cells adhere to the surfaces of the peritoneum, annexes and other pelvic organs [1-4]. The main symptoms are dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain and infertility. Although endometriosis is considered a benign condition, it shares some characteristics of cancer proliferation, such as invasion, tissue damage, neoangiogenesis and spread to distant organs [3].

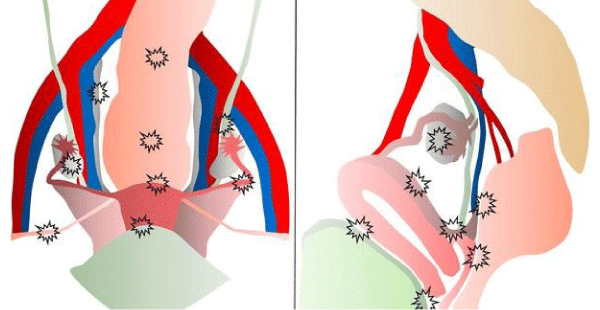

The development of cancer is a rare complication of endometriosis, and mainly in some gynecological cancers 5 and others extragonadal [3], the first case of malignant transformation was described in 1925 1 of endometriosis in the intestinal tract, 17 cases have been reported of neoplastic changes 6; the most common location being the colon and rectum-sigmoid (50% to 90%) 1 small intestine (7%), blind (3.6%) and appendix (3%), other locations are in the pleura, pericardium, navel, rectovaginal septum (13%) 7, bladder, lungs, central nervous system and even skin 1, as in scars from surgeries or previous episiotomies [1-3,8-11] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The female pelvis in (a) ventral and (b) lateral views, which indicate the sites of endometriosis.

Despite epidemiological evidence, the association between endometriosis and cancer has not been elucidated so far.

Endometriosis is hormonally dependent on estrogens, it is associated with oxidative stress, inflammatory pathways that are activated in its microenvironment [12,13], but, molecular events involved in malignant transformation are under investigation, and early molecular alterations have been identified such as the alteration of a tumor suppressor gene, the mutation of the ARID1A and loss of its encoded BAF250a [5]. The association between endometriosis and other hormone-dependent cancers particularly endometrial cancer (EC) and breast cancer (CM), share common risk factors (FR), such as hyperestrogenism, some reproductive characteristics, obesity, the administration of menopausal hormone therapy (THM) and Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) [13-15], When clinical-pathological characteristics are compared between primary CE and synchronous epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) [15], the incidence of endometriosis is higher in patients with EC than in EOC (100% vs. 35%), other malignant neoplasms such as colorectal cancer which is one of the most frequent intra-abdominal cancers in women that could exist in association with endometriosis. Uterine adenomyosis or internal endometriosis is when the ectopic endometrial glands and stroma are impregnated to the myometrium that can also be associated with an increased risk of cancer [3,14,15].

The clinical presentation of intestinal endometriosis is usually asymptomatic, or with gastrointestinal bleeding, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, defecation pain; diarrhea, constipation, rectum-vaginal colonic mass, intussusception, intestinal obstructions and intestinal perforation are observed;

Symptomatology worsens during menstruation by 40%. Imaging and endoscopy of the intestinal tract simulates other inflammatory and malignant lesions; the definitive diagnosis before surgery is difficult, only clinical suspicion can prevent it [2], consider patients with endometriosis, especially postmenopausal patients with a recurrence of symptoms [16-19] (Table 1).

| Table 1: General characteristics of endometriosis. | |||

| Sites | % | Symptomatology | Differential Diagnosisf or MRI |

| Bladder | 6.4-20 | Dysuria, hematuria, urinary retention Symptoms, suprapubic pain | Uranus remnant, epithelial and mesenchymal tumors |

| Ureters | 0.01–1 | Dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, flank pain (hydronephrosis) | CC obstruction |

| Ovaries | 20–40 | Nonspecific pelvic pain | Teratomas or hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, endometrioid cancers or clear ovarian cells |

| Round ligaments | 0.3–14 | Painful inguinal mass, nonspecific pelvic pain | |

| Retrocervical region, uterosacral ligaments | 6-9.2 | Painful symptoms, dyspareunia | Peritoneal metastasis |

| Vagina | 14.5 | dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, postcoital hemorrhage | |

| Rectosigmoid colon | 9.9–37 | Dysquecia, cyclic pain, rectorrhagia | Colorectal cancer, metastatic implants |

| RM: Magnetic Resonance imaging; CC: Cervical Cancer | |||

Endometriosis and cancer risk

Women with endometriosis are at risk of developing cancer of 87.2 per 10,000 patients/year, or risk ratio of (OR) 1.8 with a 95% CI of 1.4 to 2.4; the time to develop endometriosis cancer was 34.3 months (18.7–46.8 months) and that is when they have adenomyosis; and increases with age, with OR 2.3 for those aged 31 to 40, 2.9; for 41 to 50 years and 4.2 for those 50 years of age or older [15-17].

Imaging and pathology studies of intestinal endometriosis

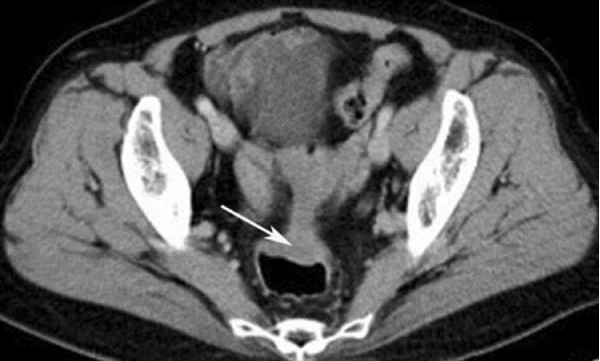

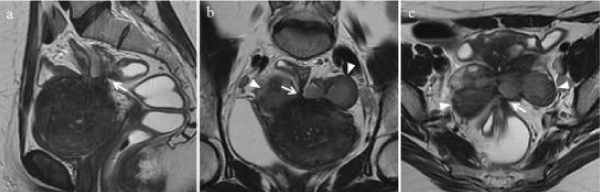

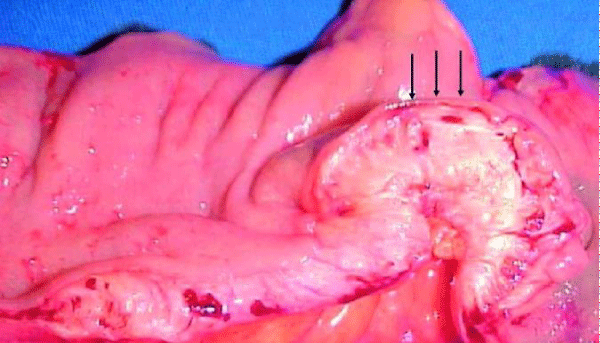

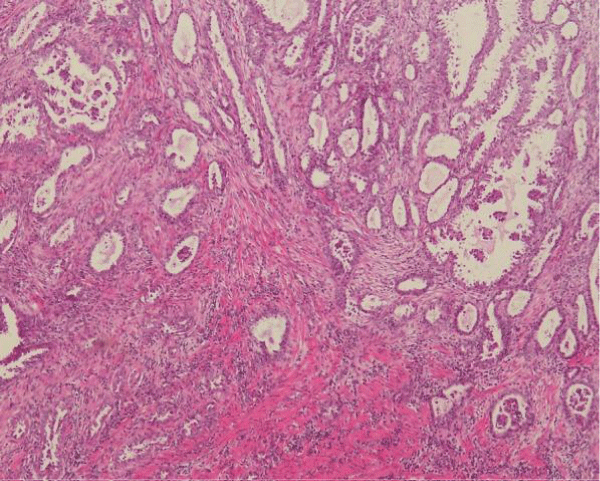

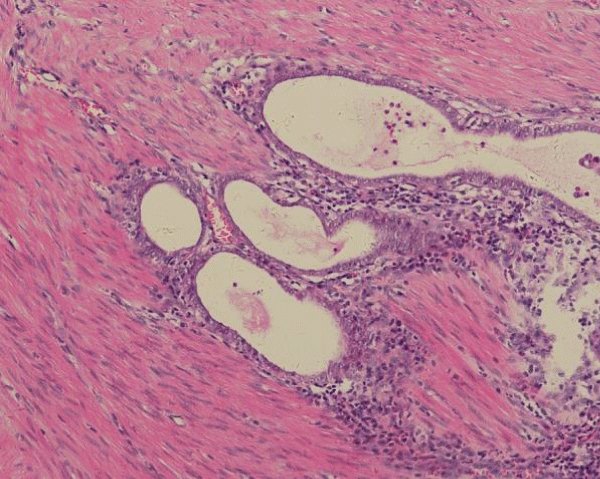

The diagnostic suspicion of intestinal endometriosis is mainly clinical, based on the symptomatology; but, the lack of pathognomonic signs makes diagnosis difficult; Even during surgery, intestinal endometriosis is confused with neoplasms, despite the use of computed tomography (CT) [1,18], Figure 2 or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the detection of wall nodules within the attached masses, when the characteristics Atypical sequences in MRI in T2 suggest a possible malignancy (Figure 3). In general it is diagnosed by histological findings after surgical resection [19] (Figures 4-6).

Figure 2: Image of computed tomography (CT) with contrast showing eccentric thickening of the wall of the rectum-sigmoid junction.

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (a) Sagittal, (b) axial oblique and (c) coronal oblique T2 weighted at T2 show spiculated hypointense areas arranged at confluent angles (white arrows) with loss of cleavage planes between the anterior surface of the sigmoid, the posterior serosa of the uterus and bilateral endometriomas (white arrowheads).

Figure 4: Macroscopic appearance of endometriotic nodule of sigmoid colon. The arrows indicate the intact mucous layer.

Figure 5: Adenocarcinoma that infiltrates the colon. Tumor cells form irregular glands.

Figure 6: Small focus of endometriosis near the tumor in the muscles of the colon.

Pathological and immunohistochemical staining (IHQ) is essential to make a diagnosis, IHQ stains, which include CK 7, CK 20, vimentin and estrogen receptors (RE) [6], are useful to distinguish between adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis and adenocarcinoma Primary intestinal [1,6]. The endometrioid glands are usually immunoreactive for CK7, RE, and stromal cells are positive for CD10 and RE. The intestinal glands express CDX2 and CK20, while showing a negative expression of CK7, RE or CD10. PAX8 was shown to be expressed in gynecological cancers [1].

Endometriosis is defined histologically as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity; common benign disease in women of reproductive age, the frequency of intestinal endometriosis varies from 3% to 34% [16], it affects the intestinal tract in 15% to 37% of patients with pelvic endometriosis [17]. Many theories about its pathogenesis have been proposed, the most accepted proposes retrograde menstruation and subsequent implantation of endometrial cells implanted in the peritoneum and pelvic viscera, which is facilitated by immune alterations; It is located in various anatomical sites, peritoneum, ovary, fallopian tubas, cervix, vagina, vulva, rectovaginal septum, uterus-sacral ligaments, intestine, rectosigmoid, bladder, uterus and skin [17].

Cancer develops in 5.5% of patients with endometriosis; 21.3% of cases originate in extragonadal pelvic sites, intestinal tumors associated with endometriosis are even more rare; in patients with pelvic endometriosis, it mainly affects the rectosigmoid colon, followed by the proximal colon, small intestine, blind and appendix. Malignant transformation of endometriosis without pelvic involvement is rare and its actual incidence is unknown; but, it simulates a neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract [1,6], in a review of endometrioid adenocarcinomas that arise in colorectal endometriosis, of 50 cases only in 22 neoplastic transformation, it was an adenocarcinoma.

The others included sarcomas and mixed Müllerian tumors; progression to cancer has been linked to hyperestrogenism and to classify cancer as a result of endometriosis, it requires histopathological criteria; proposed by Sampson for the first time in 1925 and are: 1) presence of malignant and benign endometrial tissue in the same organ; 2) that the cancer arises from the tissue and does not invade it from another place; and 3) the finding of tissue similar to the endometrial stroma surrounding the characteristic glands [6].

The symptoms of intestinal endometriosis include abdominal pain, abdominal distension, signs and symptoms of gastrointestinal obstruction, rectorrhagia, etc., depending on the segment of the affected intestine, they can be cyclic in 40% that are usually aggravated during menstruation. Preoperative diagnosis of intestinal endometriosis through imaging is difficult and rare due to other common intestinal pathologies [20]. Treatments of intestinal endometriosis depend on presentation symptoms and operative findings. Medical hormone therapy with surgery provides less recurrence of endometriosis [20,21], it is rarely successful in severe symptomatic disease or intestinal obstruction, surgery with intestinal resection and anastomosis is necessary, Superficial lesions can be removed and definitive treatment is Excision is hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oporectomy and total excision of endometrial foci by laparoscopy or by laparotomy, with multidisciplinary team; it is associated with improvements in the quality of life, it represents a safe approach to the treatment of intestinal endometriosis or colorectal cancer; the risk of subsequent colorectal cancer was elevated in patients with coexisting adenomyosis with other extragonadal endometriosis, OR, 13.04, not including carcinoma in situ; of cancers related to endometriosis, colorectal is the second most common extragonadal site for malignant transformation of endometriosis [23,24] this malignant transformation is associated with hyperestrogenism [25], the theory of malignant endometrial transformation only explains a small proportion of patients with colorectal cancer; In women with coexisting adenomyosis, there are shared etiological factors for these 2 sequential events [21]. 80% of all neoplasms associated with extragonadal endometriosis occurred in the rectum and sigmoid colon, mostly are adenocarcinomas. Adenocarcinoma that arises from endometriosis often mimics primary intestinal adenocarcinoma [1].

The possible association between endometriosis and cancer by current molecular studies through routes related to inflammation, oxidative stress and hyperestrogenism [3,12] and alterations mutations of the tumor suppressor gene PTEN or ARID1A for malignant transformation [12] and the microenvironment of endometriosis and Associated cancer share similar cytokines and mediators [23-25]. Epidemiological evidence supports molecular carcinogenesis with a link between adenomyosis and gynecological cancers, including colorectal cancer. Personalized treatment of women with endometriosis/adenomyosis is required through advice on early detection of cancer. There is no consensus on the therapeutic approach to treat malignant neoplasms associated with endometriosis, it is recommended that patients diagnosed with carcinomas associated with extragonadal endometriosis, which are limited to the lower pelvic cavity, can benefit from adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy, hormone therapy, may have a similar efficacy in malignant neoplasms associated with endometriosis with progesterone receptors [1].

Recently a new concept has been developed in the pathogenesis of endometriosis: the “neurological hypothesis”. showed an absolute correlation with the anatomic distribution of the pelvic sympathetic nervous system showed that there is a close histological relationship between endometriotic lesions of the large intestine and nerves in this area. Endometrioid lesions appear to infiltrate the wall of the large intestine preferably along the nerves, even at a distance from the palpated lesion. Endometriosis and its possible malignant changes should be taken into account in the differential diagnosis of intestinal masses in women. In addition, the clinical suspicion of malignancy should be aroused in patients with abdominal pain or rectal bleeding and a history of quiescent endometriosis [6].

Globally, cancer-associated endometriosis is very rare and it is really appropriate to consider it a premalignant condition; but, there is considerable controversy in the literature about the relationship between endometriosis and cancer [6]. Due to the malignant potential, patients with endometriosis should have adequate hormonal management even after surgery and estrogens without opposition should generally be avoided in these patients [16,25].

Endometriosis is associated with an increased risk of cancer, including colorectal cancer mainly when coexisting with adenomyosis. Studies on the association of adenomyosis and the risk of colorectal cancer are needed to clarify whether the malignant transformation of colorectal endometrial implants.

- Li N, Zhou W, Zhao L, Zhou J. Endometriosis-associated recto-sigmoid cancer: a case report BMC Cancer. 2018; 18: 905.

- Muthyala T, Sikka P, Aggarwal N, Suri V, Gupta R, et al. Endometriosis presenting as carcinoma colon in a perimenopausal woman J Midlife Health. 2015; 6: 122–124. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4604671/

- Krawczyk N, Banys-Paluchowski M, Schmidt D, Ulrich U, Fehm T. Endometriosis-associated Malignancy Geburtsh Frauenheilk 2016; 76: 176–181. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4771509/

- Vaarala MH, Hellstrom P, Santala M. Is the incidence of urinary bladder endometriosis increasing? Figures from Finland. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2010; 70: 55–59.

- Vargas-Hernández VM. La endometriosis como factor de riesgo para cáncer de ovario. Cir Cir. 2013; 81: 163-168.

- Marchena-Gómez J, Conde-Martel A, Hemmersbach-Miller M, Alonso-Fernández A. Metachronic malignant transformation of small bowel and rectal endometriosis in the same patient World J Surg Oncol. 2006; 4: 93. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1712233/

- Vargas-Hernández VM. Endometriosis rectovaginal: ¿tratamiento médico o quirúrgico? Revista Mexicana de Cirugia del Aparato Digestivo 2015; 2: 62-67.

- Li N, Zhou W, Zhao L, Zhou J. Endometriosis-associated recto-sigmoid cancer: a case report BMC Cancer. 2018; 18: 905.

- Kobayashi S, Sasaki M, Goto T, Asakage N, Sekine M, et al. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis of the rectosigmoid. Dig Endos. 2010; 22: 59–63. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20078668/

- Katsikogiannis N, Tsaroucha A, Dimakis K, Sivridis E, Simopoulos C. Rectal endometriosis causing colonic obstruction and concurrent endometriosis of the appendix: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011; 5: 320. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21774792/

- Pisanu A, Deplano D, Angioni S, Ambu R, Uccheddu A. Rectal perforation from endometriosis in pregnancy: case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16: 648e51. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2816281/

- Worley MJ, Welch WR, Berkowitz RS, Ng SW. Endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer: a review of pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013; 14: 5367–5379. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23466883/

- Lai CR, Hsu CY, Chen YJ, et al. Ovarian cancers arising from endometriosis: a microenvironmental biomarker study including ER, HNF1ss, p53, PTEN, BAF250a, and COX-2. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013; 76: 629–634.

- Yamanoi K, Mandai M, Suzuki A, Matsumura N, Baba T, et al. Synchronous primary corpus and ovarian cancer: high incidence of endometriosis and thrombosis. Oncol Lett. 2012; 4: 375–380. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3439173/

- Nomelini RS, Ferreira FA, Borges RC, Adad SJ, Murta EFC. Frequency of endometriosis and adenomyosis in patients with leiomyomas, gynecologic premalignant, and malignant neoplasias. Clin Exp Obst Gynecol. 2013; 40: 40–44. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23724504/

- Ishii M, Yamamoto M, Tanaka K, Asakuma M, Masubuchi S, et al. Intestinal endometriosis combined with colorectal cancer: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2018; 12: 21. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5789683/

- Uchiyama S, Haruyama Y, Asada T, Nagaike K, Hotokezaka M, et al. Rectal endometriosis masquerading as dissemination in a patient with rectal cancer: report of a case. Surg Today. 2010; 40: 672–675.

- FotiPV, Farina R, Palmucci S, Vizzini IAA, Libertini N, et al. Endometriosis: clinical features, MR imaging findings and pathologic correlation Insights Imaging. 2018 Apr; 9: 149–172. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29450853/

- Charatsi D, Koukoura O, Ntavela IG, Chintziou F, Gkorila G, et al. Gastrointestinal and Urinary Tract Endometriosis: A Review on the Commonest Locations of Extrapelvic Endometriosis Adv Med. 2018; 2018: 3461209. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30363647/

- Young S, Burns MK, Di Francesco L, Nezhat A, Nezhat C. Diagnostic and treatment guidelines for gastrointestinal and genitourinary endometriosis. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2017 Dec; 18: 200–209. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29278234/

- Chen PC, Chao SC, Hsu KF, Lee CT, Lee JC. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from colonic endometriosis in a Lynch syndrome patient. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012; 27: 681–682.

- Nasu K, Okamato M, Kawano Y, et al. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from intestinal endometriosis. JEPPD. 2014; 6: 112–118. PubMed: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6148997/

- Worley MJ, Welch WR, Berkowitz RS, Ng SW. Endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer: a review of pathogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013; 14: 5367–5379. PubMed: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23466883/

- Lai CR, Hsu CY, Chen YJ, et al. Ovarian cancers arising from endometriosis: a microenvironmental biomarker study including ER, HNF1ss, p53, PTEN, BAF250a, and COX-2. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013; 76: 629–634.

- Vargas-Hernandez VM, Tovar-Rodriguez JM, Vargas-Aguilar VM. Oncogenic Risk of Endometriosis. Austin J Reprod Med Infertil. 2015; 2: 1028.